|

|

|

|||||||

Policy: |

|||||||

"The greater rights of the accused is an example of the modern respect for process, as opposed to result, but that's another rant" I know what you're talking about (or at least think I do), but I would be interested in reading more about this. Planning on writing out such a rant any time soon? —Random Internet Guy

The respect for the rights of the accused reflects two trends in modern thought. 1. Valuing process over prejudgment. 2. Assessing situations abstractly rather than particularly. This rant covers point #1. Modern thinkers value process over prejudgment because process is a way to control human fallibility (without ever eliminating it). The scientific method is an example of a modern process that resists the human tendency to err. It's clear that people are prone to making false (and often self-serving) conclusions about nature and its laws. The scientific method provides, first, a barrier against unverifiable or verifiably false ideas and, second, a way to correct errors. Science still makes mistakes (see blood, mongoloidism, racial genetics), but it eventually corrects them. The modern legal process does much the same thing. It protects citizens from other citizens' penchant for judging and punishing. It makes notpretense to perfection. In fact, error is built into the system (see preventative incarceration). The founders of our legal system understood error to be inevitable. Some guilty people would inevitably go free, and some innocent people would inevitably be punished. Lawmakers faced the ethical dilemma of deciding which sort of errors to favor. If they built the system with too many rights for the accused, guilty people would too often go free. If they built the system with too few rights for the accused, innocent people would too often be punished, even executed. So they built the system to favor the accused. They knew that they were letting more guilty people go that way, but they also knew they were endangering fewer innocent citizens. They knew that a government willing to endanger the lives and liberties of innocent citizens was tyranny, and they preferred the personal crimes of criminals to the institutional crimes of the state. As laudable as that sentiment may be, the resulting legal system is fallible. It's designed, in fact, to be intentionally fallible in one direction. No one imagines it to be perfect. Such a system only arises out of humility, out of the knowledge that best intentions go astray. The modern thinker practices this humility, not only with law but also with science and religion. But there are plenty of 19th century thinkers out there who don't practice this humility. They consider their religious, political, and scientific ideas to be certain truths, not their best guesses yet. They believe those who are outside their religious "tribes" to be lost. They want the 10 Commandments posted in courthouses and enforced by the police. They want their natural histories (or, rather, supernatural histories) taught in public schools as science. —JoT top |

|||||||

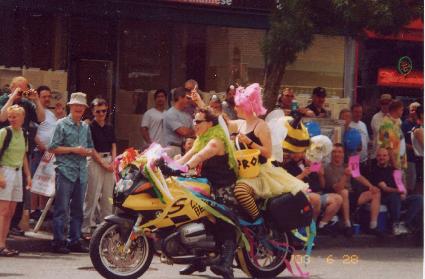

Gay Pride Parade, Seattle, 2003 click for more |

|||||||